In 19th-century rural Ireland, the blacksmith and the blacksmiths Horseshoe shaped forges was at the heart of community life. His forge was more than just a workshop—it was a gathering place where neighbours exchanged news while waiting on a repair or a shoeing job. In an age before mass industry reached the countryside, the smith’s skill kept farming, transport, and daily life running.

The Blacksmith’s Work

The work was physically demanding and wide-ranging. A blacksmith shod horses, but that was only part of his trade. He made and repaired ploughs, spades, scythes, axes, hinges, nails, gates, and cart fittings. In farming districts, he was indispensable: if a plough broke at the start of the planting season, it was the smith who restored it in hours rather than days. In coastal or bogland areas, he might fashion specialized tools for fishing or turf-cutting.

Smiths relied on skill as much as strength. They judged iron by the color of its glow, shaping it with hammer blows in rhythm with the bellows’ breath. Each job required precision—too much heat, and the metal lost its temper; too little, and it would crack under the hammer. Apprenticeships could last years before a young man was trusted with important work.

The Horseshoe Shaped Forge

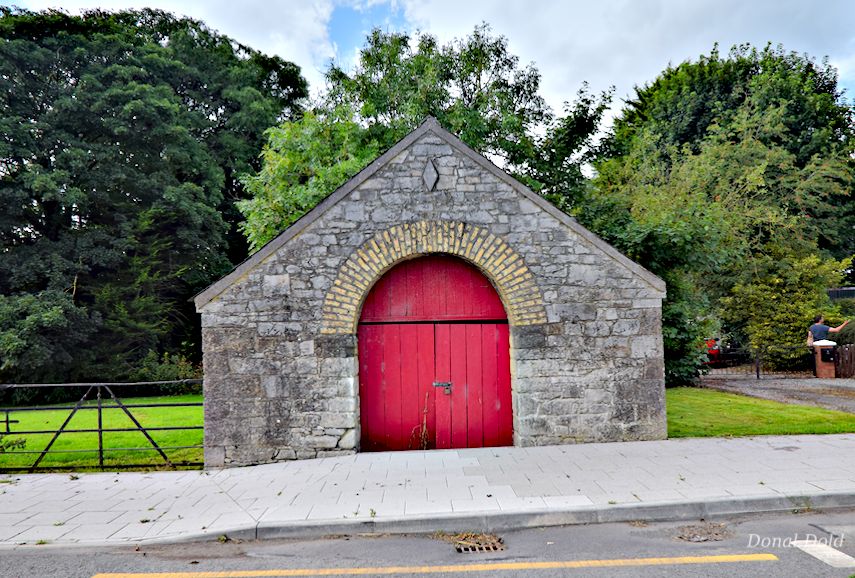

The forge was the blacksmith’s domain. Many were simple, stone-built cabins with a thatched or slated roof, a wide door for animals and carts, and a chimney for the smoke. Inside, the essentials were the hearth, bellows, anvil, tongs, and hammers. The fire glowed constantly, and the clang of iron on iron carried through the village.

Some forges, especially in certain regions, were distinctively shaped like a horseshoe. This design wasn’t just decorative. The broad curve gave space for large animals to be led in and turned, while also symbolizing the trade itself. The horseshoe shape was practical and emblematic—anyone passing by knew immediately they were at a smith’s door.

Social Role

Beyond their craft, blacksmiths held a respected position in rural Ireland. Their work carried an air of mystery: they “tamed” fire and bent iron to their will. Folklore often cast them as half-magician, half-artisan, with a touch of danger about their power. In villages, the forge doubled as a hub of conversation and storytelling. Long evenings might see neighbors lingering by the fire, swapping tales and debating politics, while sparks from the anvil lit the dark.

By the end of the 19th century, the blacksmith’s world was beginning to change. Industrial production and factory-made goods slowly reduced the demand for handmade tools. Yet in the Irish countryside, far from railways and cities, the smith remained essential well into the early 20th century, a figure of both necessity and tradition.

I have found six, blacksmiths Horseshoe shaped Forges, in my local County of Offaly.

Curragh

built c.1870.

The craftsmanship of the stone blocks of the arch framing, shows remarkable craftsmanship, highlighted by crisp nail-head decoration and the clear groove of the horseshoe arch

Clonbulloge

Built 1865-1870

Gurteen

After its use as a forge, the building later functioned as a shop. Traces of the former post box remain visible on the wall.

Killeigh

Once a busy forge, this building is now a home, standing directly on the street front. Despite modern extensions and alterations, its historic façade endures, preserving the spirit of the original structure

Rahan

There was a forge on this site for over 200 years.

Walsh Island

I could not find information about this forge.